Welcome to Issue #023 of The Forcing Function - your guide to delivering the right outcomes for your projects and your users.

✍️ Insights: Bad news has a way of surfacing if you try to hide it.

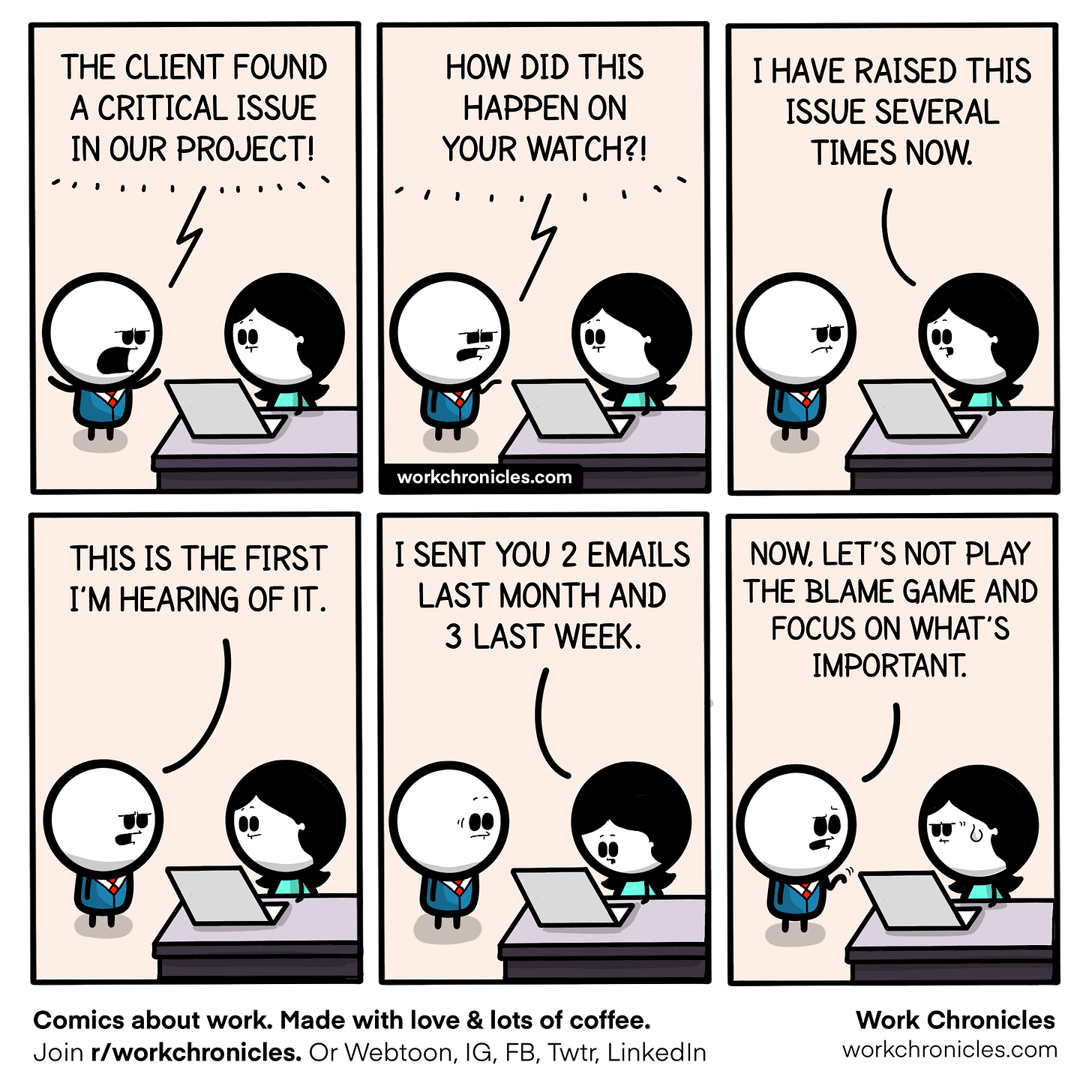

🤔 Made me think: When your warnings go unheeded.

👨💻 Worth checking out: Why some bad news should be delivered in person.

✍️ Insights

Bad news has a way of surfacing if you try to hide it.

“I don’t know what the rest of you are smoking but we are behind schedule and the quality simply isn’t there.”

It was another Friday morning and we were coming to the end of the weekly all-hands programme update. Starting with the programme manager and working through the rest of the team leader. The messaging did vary but it was always within the envelope of we’re making progress, here’s an issue or two we’re resolving, and there’s nothing to worry about.

Now it was the turn of the testing team leader. Unlike their peers, she wasn’t interested in keeping the peace. Instead, she delivered a brutal yet accurate assessment of our predicament.

It definitely wasn’t fun to hear but their honesty was appreciated by the executive sponsor.

Now you could argue that she was being overly pessimistic or she was playing politics to absolve her team of blame in case the programme did fail. From my perspective, it was clear that the executive sponsor wasn’t naive and he was, in fact, highly knowledgeable about the details. So, it was better to be upfront with him than to attempt to cover up the inevitable bad news.

But, just because it’s the right thing to do doesn’t mean that it’s the easy thing to do.

In this case, her frankness gave those of us “permission” to be a bit more open about our own bad news. It wasn’t universal, politics and optics are always ever-present and shouldn’t be negletcted. But, the transparency was an improvement than the glossed facade that was being projected.

A lesson from hiding bad news badly

Days before Christmas 2022, LastPass belatedly admitted that it had been breached again and the attackers had managed to obtain a copy of their customer password vaults.

That particular gem was buried five paragraphs into their statement.

If you’re unfamiliar with this company, they provide a cloud-based password management service which helps you generate and easily use strong passwords for logging into your accounts.

Their framing of what happened and the risk to their customer base could best be described as an exercise in damage limitation. At worst, they are deliberately burying their failures and grossly misleading their customers to think they are safe when, in all likelihood, they are not.

Take this example, courtesy of Wladimir Palant (cybersecurity expert and creator of Adblock Plus) excellent vivisection of LastPass’s statement.

[From Lastpass’ statement] These encrypted fields remain secured with 256-bit AES encryption and can only be decrypted with a unique encryption key derived from each user’s master password using our Zero Knowledge architecture.

[From Palant’s analysis] Lots of buzzwords here. 256-bit AES encryption, unique encryption key, Zero Knowledge architecture, all that sounds very reassuring. It masks over a simple fact: the only thing preventing the threat actors from decrypting your data is your master password. If they are able to guess it, the game is over.

Personally, I’m astounded they decided that this was the right approach to take. Though, given that the way the’ve handled their many security incidents since 2011, perhaps I shouldn’t be.

Disclaimer: I’m a paying customer of 1Password which provides a competing service.

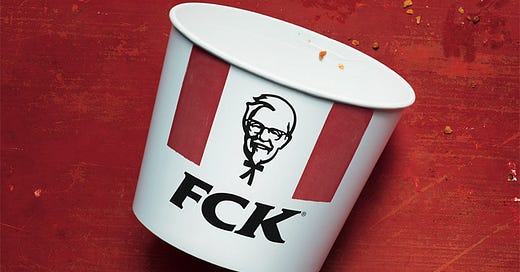

A lesson from how KFC was FCK’ed

On Valentine’s Day 2018, KFC UK’s new logistics supplier (DHL) took over and promptly caused a UK shortage of fried chicken.

In fairness, it wasn’t entirely DHL’s fault as two road traffic accidents in quick succession closed off access to KFC’s single distribution depot. However, that was exacerbated by DHL’s introduction of a new depot, with new IT systems, and new staff. Unfortunately, they weren’t fully set up or throughly tested ahead of the switchover and 75% restaurants closed because they had no chicken.

The disruption lasted for weeks and the police even had to tell customers not to call them about the shortage!

However, how KFC handled it was a masterclass in not only owning their mistakes but to use it to rebuild trust with their customers.

They quickly acknowledged there was a shortage and were open about why it had happened.

They provided clear information and reassurance about what was happening to control the narrative. Such as confirming that their restaurant workers would still get paid even if the restaurants were closed and providing a page for customers to check which restaurants were back open and what they could serve.

They made light-hearted banter about the shortage and owned the situation by taking the risk to temporarily re-brand from “KFC” to “FCK” when publicly apologising.

As a result, their brand reputation didn’t just rebound after the #KFCCrisis was over but had actually improved.

Focus on context and options

Aside from getting you to crave KFC, both stories are the sides of the same coin.

You may not think that managing a shortage of fried chicken is anywhere on the same level as managing a cybersecurity breach. Yet both suffered a critical incident on their core product and their entire raison d’être. What’s the point of a password manager if it can be attacked and what’s the point of a fried chicken restaurant with no chicken?

For LastPass, they obfuscated and were rightly called out for doing so. For KFC, they took the hard decision to own up and accept responsibility. Even after an dip in their share price during #KFCCrisis their market share went up 1% - a major achievement given what happened and the hyper-competitiveness of the fast food market.

To this day, I still don’t find it easy to deliver bad news. My perfectionist tendencies abhors this as it’s a sign of failure - regardless if I was directly responsible or not. Over the years, I’ve come up with this set of guidelines which I’ve found helpful to follow:

Be transparent and honest about what happened and the impact. But also, frame it in a context that’s clear, unambiguous, and doesn’t “bury the lede”.

Be open about what I don’t know (yet) or am unsure of - especially if the situation is still highly volatile.

Be reassuring in addressing the key concerns and, where do you have confidence, share potential and available options.

Be communicative on a regular basis and don’t allow fear, uncertainty, and doubt to obscure or distort your core messaging.

Most of all, be aware of what risks are going to turn into critical issues. No-one likes being surprised with bad news at the last moment.

🤔 Made me think

When your warnings go unheeded.

Whilst you may choose to do the right thing and be honest about what’s happening, not all senior stakeholders are equally sympathetic. They may be too busy to hear your message, they may not understand what it means, or they may be playing politics.

That doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t try. You’re not Cassandra who had the gift of prophecy but was cursed by Apollo that no-one would believe the ones that were true. You do have agency to continue communicating and to land your message in different ways and formats.

🧑💻Worth checking out

🔗 The car crash of terminating an employee via video chat | Up In The Air (2009)

Certain types of bad news, such as letting someone go, are far better delivered face-to-face despite all the technology we have today.

🖖Until next Thursday ...

If you enjoyed this newsletter, let me know with the ♥️ button or add your thoughts and questions in the comments. I read every message.

And, if your friends or colleagues might like this newsletter, do consider forwarding it to them.

For now, thank you so much for reading this week's issue of The Forcing Function and I hope that you have a great day.

PS: Thanks to P for reading drafts for me.

It's always better to get ahead of bad news. Procrastinating on it also tends to make it worse. Thanks for the reminder!

Great Article this week. I think regular conversation around quality of delivery and general comms between teams in a programme will always help buffer the delivery of bad news