#041: No story, no impact, no change.

Welcome to Issue #041 of The Forcing Function - your guide to delivering the right outcomes for your projects and your users.

✍️ Insights: Always be in control of the narrative lest someone else’s narrative controls you.

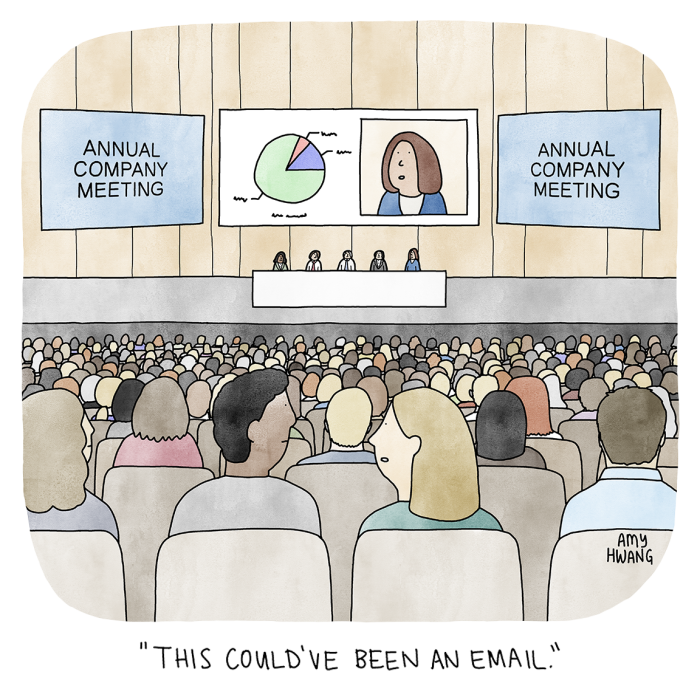

🤔 Made me think: This could’ve been an email.

👨💻 Worth checking out: Explaining “fire”.

✍️ Insights

Always be in control of the narrative lest someone else’s narrative controls you.

Growing up as a kid, my parents told me all sorts of things to get me to do what they wanted.

One of my favourites my Mum telling me to always eat all my rice. Otherwise, every grain of rice that I left in the bowl would mean my future wife would have another spot on her face. On reflection that’s quite an unusual incentive to give a child but, nevertheless, I made sure to clear my bowl.

My wife does have very clear skin so perhaps my Mum was right after all. 😉

How a good story defies the facts

What didn’t have much truth in it was the reason I was told to eat my carrots.

Whilst I’m not averse to eating vegetables, I just don’t like the taste of carrots. But, my primary school teachers always insisted that I finish them whenever they were served at lunch. Their incentive - because it would help improve my vision - especially in low-light.

Let’s get the facts out of the way. The Vitamin A in the beta carotene of a carrot is good for your overall eye health. But it doesn’t make your eyesight significantly better - let alone in low light.

So where did this story come from?

During World War II, the German Luftwaffe conducted The Blitz - a mass aerial bombing campaign against British cities and industry - . By 1940, to avoid the defending Royal Air Force (RAF) fighters, the Luftwaffe switched to night bombing. At the time, fighters relied on visually sighting their target and doing this at night was incredibly difficult and German bomber losses were minimal.

That was until radar technology matured enough for it to be mounted on a fighter and for it to be effective in detecting enemy bombers so that they could be intercepted before they crossed the English Channel.

To avoid the Germans changing tactics once again, the British wanted to keep their new technological superiority hidden from the Germans. However, they needed to provide a different explanation for the growing success of their RAF in repelling the Luftwaffe’s bombing raids. So, the UK’s Ministry of Information came up with propaganda campaign based around RAF pilots eating excess quantities of carrots to give them better night vision.

It didn’t matter that the story wasn’t true. What mattered is that the story was plausible, it was simply explained, and it was popularised through the various propaganda campaigns. So much so that people still believe this story to this day even though it’s a myth.

“What you do in this world is a matter of no consequence. The question is what can you make people believe you have done.”

Sherlock Holmes | Fictional detective created by Arthur Conan Doyle

The power of stories in change

So what’s a story about eating carrots that turned out to be a myth got to do with business analysis?

Unlike a role that sits squarely in the “run the business” side of an organisation, as a business analyst (BA), I’m usually embedded on the “change the business” side. Whether that’s making minor business-as-usual changes to doing enterprise-wide target operating model changes. And those changes inevitably impact people - both within the organisation as well as external stakeholders.

Processes, data, and technology all matter and are all important when landing and embedding change in an organisation. But, more often than not, I find that the most important factor is how the people affected by the change react to it. They can either ignite the drive towards the outcomes you’re looking to achieve or extinguish them.

If there’s one piece of hard-won advice I can give as a BA to anyone on the “change the business” side, it’s this.

You may be accustomed to the fast pace of change because that’s the world you inhabit. But your stakeholders mostly likely aren’t. They are going to be surprised by how quickly change happens not just for them but to them.

Some will look to rise to the challenge. Some will resist to what’s being done to them and will do what they can to thwart you. Most will prefer to stay where they are in the belief that it’s “better the devil you know”.

20+ years ago, when I first studied business analysis, the emphasis of the discipline was on the requirements engineering side. More on doing the analysis and artefacts for the discovery and design phases of a project. Less on the delivery and deployment phases where it was primarily about the BA providing subject-matter-expertise support.

A lot has changed since then with the role of a BA expanding, amongst other things, to include managing business change (alongside change management specialists). And rightly so because we sit at the intersection of the “run the business” side and the “change the business” side. From that optimal position, we’ve analysed our users’ pain points, we’ve helped shape the solution accordingly, and so, we can clearly articulate what the benefits are and how they’ll look.

Most importantly, we have the opportunity to craft the story of these changes so that they resonate with each stakeholder group.

Not just to allay their concerns about the pain the changes are going to bring but also to create that sense of a shared endeavour, for a shared outcome, on a shared journey from the old world to the new.

An anti-lesson

Now all of that might sound like it comes out of an IT consultancy playbook but let’s consider the alternative.

One project I worked on (for a very short period) had a storied vision but not a compelling story. So, the users simply weren’t persuaded that the changes were worth the pain needed and, instead, fiercely guarded the status quo. They were so jaded by the constant churn of change with no narrative about why projects were happening or how they were all connected in a master plan.

It didn’t matter than the project was going to deliver the equivalent of new Eden for them. That it would address their longstanding complaints and concerns. Or, that it would free them from the low value aspects of their work so that they could focus on the more inspiring aspects.

Because its story was told so poorly, it didn’t catch the users’ attention and they simply wrote it off. Instead, the users made up their own story that better fitted their beliefs, their biases, and the outcome that they wanted. And like the carrot and the night vision story, it was one that was compelling to them - even if it wasn’t factually true.

How many projects have been seen as or have turned out to be failures because their story weren’t told as well as they could’ve been?

As a BA, our bread and butter are our user stories - the formatted way in which we write our requirements in. But, to effectively land those changes, we also must lift ourselves out from that detail to the overarching story that we’re telling our stakeholders. Is it compelling enough for them to understand that the change is being for them, the benefits they’ll get, and why it’s worth the pain of changing from the status quo?

If not, then be warned that they’ll come up with their own story. One that, at best, you won’t agree with. And, at worst, you’ll be constantly fighting against.

🤔 Made me think

This could’ve been an email.

It never ceases to surprise me how uninspiring and mundane group meetings can be - like all-hands company meetings down to the humble training session.

For the latter, they can be an excellent opportunity to show users the tangible benefits and to galvanise both their support and their enthusiasm for the upcoming changes. Especially so for those users who haven’t had much direct engagement until attending the training session.

But all of that can be squandered away with an dull trainer who just reads off slides, who doesn’t really know what’s changed and so can’t answers questions, and who is so rigid with getting through the training material that they don’t take the time needed to bring their audience with them.

I think that we’ve all been in training sessions like that and we’ve all switched off at some point.

As the saying goes: “if you can’t do it right, then don’t do it all”. So, rather than waste your users’ time and creating ill-will, you’d be better off doing something simpler that you can do right.

PS: One of the reasons for why there’s usually a boring all-company conference before the summer / Christmas party in the evening is not just to bring people together or to give a mass update. It also allows the event (including the social) to be tax deductible.

🧑💻Worth checking out

📺 Explaining “fire” | BBC “Fun To Imagine” Richard Feynman

Physics was one of those subjects that I never quite got at school. I did well enough to pass my GCSE in the subject, but I never continued with it. It just seemed so abstract that I was bored by the theory.

But listen to Feynman, a Nobel-winning theoretical physicist, explain what fire is. He explains the theory in such a way that it was both accessible and compelling to the layperson. Whilst the story he weaves is exciting, what makes it resonate so well with his audience that he himself is still excitable about it.

A remarkable skill and attitude to have given describing fire is so much simpler than his work on quantum mechanics which earned him the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physics.

This is just one of six episodes recorded and it’s worth watching all of them here.

🖖Until next Thursday ...

If you enjoyed this newsletter, let me know with the ♥️ button or add your thoughts and questions in the comments. I read every message.

And, if your friends or colleagues might like this newsletter, do consider forwarding it to them.

For now, thank you so much for reading this week's issue of The Forcing Function and I hope that you have a great day.

PS: Thanks to P for reading drafts for me.