#020 - What surviving on Mars teaches us about managing risk

Welcome to Issue #020 of The Forcing Function - your guide to delivering the right outcomes for your projects and your users.

✍️ Insights: Hope for positive risks. Manage the negative risks.

🤔 Made me think: The worst risks aren't the ones that first come to mind.

👨💻 Worth checking out: Chaos at the Top of the World.

📧 With the support and encouragement of the Newsletter Launchpad community, I'll be moving this newletter into the Substack network. All being well, that'll happen by next week's issue and previous issues will be migrated too.

✍️ Insights

Hope for positive risks. Manage the negative risks.

Delivering a project is inherently risky.

A project requires making a change to the status quo. But, by upending the established order there's now the potential that the outcome is markedly different to what you imagined. The future is uncertain whilst our ability to consistently and accurately predict what will happen is, at best, questionable.

That, essentially, is what risk is: the gap between what actually happens and what you expect to happen.

In an idealised world, any gap would be a positive risk. That's a good outcome where what happens is better than what you expected. Think of these as opportunities for you to take advantage of.

For one of my clients, that was budgeting contingency to deal with difficult stakeholders. Only to find that after earning their trust they were easy to work with. I then re-allocated that "extra" time and effort to deliver a more complete and polished solution.

Sadly we don't live in that mythical place. More often than not, gaps are negative risks. The ones that can lead to issues that range from inconsequential inconveniences to catastrophic crises. You deny such risks at your peril.

For only the naive or the Pollyannish believe that everything will just, somehow, work out for the best.

What space exploration can teach us about managing risk

On 11 December 1972, Apollo 17 landed on the moon. It was the last time that humans walked on the Moon. 50 years later, on 11 December 2022, Artemis 1 splashed down having successfully completed two lunar flybys.

Space exploration is one of the most complex and riskiest projects that humans can do. Doing that with a crew and safely returning them takes that to another level. NASA's Artemis project, whose long-term goal to land humans on another planet for the first time, takes that to the extreme.

For them to get to Mars, for you to give your project the best chance to succeed, it's better to manage your risks than to fire-fight after they've ignited into issues.

If you'll indulge me, let's take a look at the risk of surviving on Mars but through the lens of one my favourite sci-fi books "The Martian" by Andy Weir.

It tells the story of how astronaut Mark Watney is stranded on Mars and how he has to improvise to survive until he can be rescued. For Weir, to make his story realistic, he studied orbital mechanics, astronomy, and human spaceflight. For me, it's a fun way to explain how you manage risk using the 4 T's Framework.

Terminate: Avoiding the risk

Scenario: At the start of the story, a dust storm approaches the Mars base. It unexpectely becomes so powerful that it can topple the base's ascent vehicle. Without it, the astronauts can't get back to orbit.

Action: They follow standing orders to end their mission early and lift off to return to Hermes - their mothership that will ferry them to Earth.

Outcome: By leaving immediately, most of the team avoids this weather risk though the storm ends up stranding Watney through a freak accident.

Treat: Reduce the likelihood / impact.

Scenario: Watney only has a quarter of the food he needs for rescue in 4 years time and realises that he must grow more to survive.

Action: He finds potatoes to use as seeds and manages to grow a potato crop.

Outcome: By farming, Watney mitigates his starvation risk.

Tolerate: Accepting the risk.

Scenario: Watney can't use the rover's heater as it kills the battery which limits the range he can travel. But Mars averages -100 Celsius so he needs to be warm.

Action: He installs the nuclear generator for heat. The same one that they buried upon landing on purpose. The very one that'll kill him if it ruptures.

Outcome: By virtue of its robust design, Watney accepts that it's unlikely to leak.

Transfer: Hand over / share the risk.

Scenario: Whilst Watney struggles to survive, NASA internally debates whether to send the Hermes crew back to save him (thus risking all their lives) or to leave him to die (but saving the crew).

Action: The Hermes crew is unaware of this. When they do find out, because of their esprit de corps, they override the controls and make the decision for NASA.

Outcome: By committing mutiny, the crew forcibly takes this mission risk away from NASA to themselves.

Business analysis and risk management

Managing risk isn't simply something that the project manager does. It isn't documenting a risk log that gathers dust. It's not (completely) an exercise in covering your butt.

It's what everyone on the project team needs to do.

Here's how applying this framework on one project helped me be a better business analyst and successfully deliver it:

When defining the project: Terminating a technology risk by recommending a platform that was expensive but met our needs over one that was cheaper as missing features were on the roadmap.

When analysing requirements: Treating the stakeholder risks by doing effective stakeholder management to ensure buy-in and reduce the likelihood that a powerful stakeholder would derail delivery.

When building the components: Tolerating an external risk of using 3rd party software components as they were for a non-critical part of the solution.

When testing the solution: Transferring the security risks by engaging independent penetration testers to robustly evaluate our solution.

It doesn't matter if it's your responsibility as it'll impact the project and you regardless. As the British Transport Police succinctly say in their public safety messaging: "see it, say it, sorted".

So, see the risk, communicate the risk, manage the risk.

🤔 Made me think

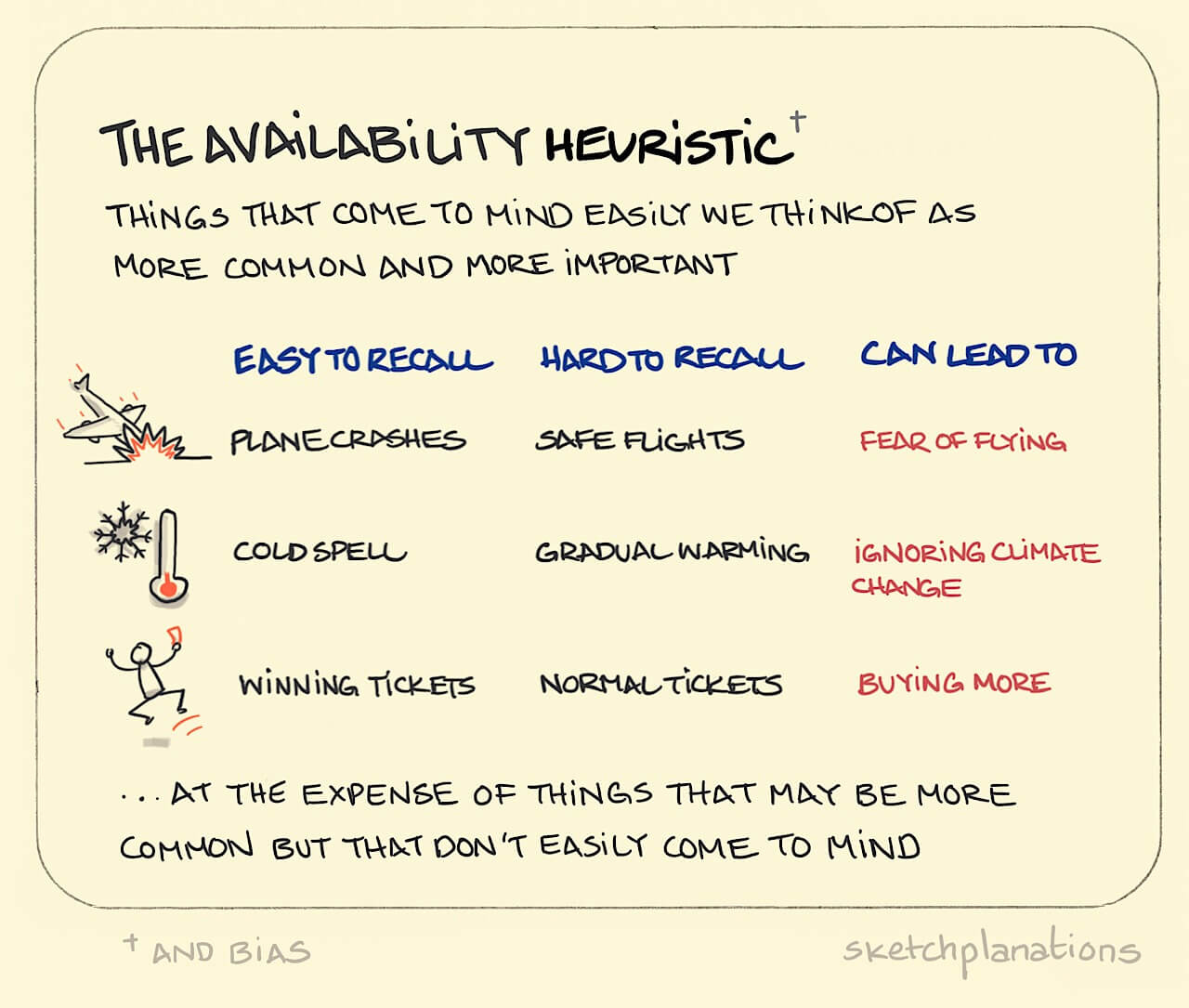

The worst risks aren't the ones that first come to mind

When it comes to considering risks, it's easy to fall into the trap that because something hasn't happened yet (or not recently) that you either believe that it isn't likely to happen or you're not even aware that it can happen.

🧑💻Worth checking out

🔗 Chaos at the Top of the World | GQ

“For God's sake,” another climber exclaimed, raising his arms in disgust. “Why is she not moving?”

Of all the risks of mountaineering, I would never have considered dying because I was stuck behind someone who was too inexperienced, who was too scared, and who was blocking the only route.

You can read the full article by Joshua Hammer at GQ.

🖖 Until next Thursday ...

If you enjoyed this newsletter, let me know with the ♥️ button or add your thoughts and questions in the comments. I read every message.

And, if your friends or colleagues might like this newsletter, do consider forwarding it to them.

For now, thank you so much for reading this week's issue of The Forcing Function and I hope that you have a great day.

PS: Thanks to P for reading drafts for me.