#017 - Lost in translation

Welcome to Issue #017 of The Forcing Function - your guide to delivering the right outcomes for your projects and your users.

✍️ Insights: Even when you speak the same language you're easily misunderstood.

🤔 Made me think: How different countries negotiate differently.

👨💻 Worth checking out: The "Four Candles" sketch.

✍️ Insights

Even when you speak the same language you're easily misunderstood.

The English language is wonderfully versatile but that versatility can catch you out.

Take the "F" word for example. It's one of the most versatile ways to express a variety of emotions including: success over the odds, outright surprise, dismay at a bad outcome, sheer anger, and being dismissive. Even writing those examples out, doesn't quite convey just how succinct and how direct using it can be.

The catch is whether or not you understand the tone, the intention, and the context when it's used. If that wasn't difficult enough, you also have to figure out whether they're joking, if they're being ironic, or do they actually mean it. Especially if it's as short as "F' this or "F" off.

Its ambiguity is both its strength and its weakness.

That ambiguity extends to the rest of the English language. The multitude of synonyms that each add a different nuance to what you're communicating out. And how you're interpreting what you're receiving.

Paraphrasing Murphy's Law: "anything that can be misunderstood, will be misunderstood".

Over countless software delivery projects I've seen that happen time and time again in my role as a business analyst. Sometimes resulting in hilarious facepalm moments and sometimes resulting in painful project post mortems about why we didn't deliver what we promised.

As business analysts, having command over language is crucial not just to our success but to our project's success too. After all, one of our many roles is to translate what our stakeholders tell us into requirements for our developers and testers to use. And, if we can't understand what's needed, then how are they going to?

And if we get it wrong in severe scenarios, it can lead to devastating and costly consequences. As these two historial examples painfully illustrate.

The mistranslation of "mokusatsu" and the bombing of Hiroshima

On 16 July 1945, the US successfully conducted the first atomic bomb test.

10 days later, on the 26 July, the Allied leaders convened in Potsdam, Germany. There they issued the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender. This included a warning to Japan that any rejection would invite "prompt and utter destruction".

Japan was down but she wasn't yet out of the fight. She still had an empire in Asia Pacific, she still had millions of active duty soldiers willing to die for their motherland, and she still had hundreds of thousands of Allied POWs in captivity. For them, the war was not over and it wasn't yet lost.

In Japanese culture, it's difficult to directly respond with "no". It's considered impolite, particularly in formal settings including diplomacy. So you can leave a meeting believing that they have agreed to your proposal when, in fact, the opposite is true.

When asked by reporters about the Potsdam Declaration, Japan's Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki simply replied with his sidestep response: mokusatsu.

Derived from the word for silence, he apparently meant "no comment". Due to carelessness or bias, the international news agencies chose to use the alternate meaning "treat with silent contempt" and mistranslated his response as "not worthy of comment".

Partly due to this mistranslation, a mere 10 days after the Potsdam Declaration was issued, the US bomber "Enola Gay" dropped the atomic bomb over Hiroshima.

Understanding fails even within the same language

278 days after launch and 200 million kilometres later, NASA's Mars Climate Orbiter had successfully made the approach for Mars. On 23 September 1999, as scheduled, the spacecraft made its insertion burn to put it into orbit. 8 days later NASA confirmed loss of signal and the complete loss of the spacecraft.

The cause was almost unbelievable.

The spacecraft used NASA's navigation software which operated in metric units (e.g. newton seconds). Unfortunately, the guidance software developed by Lockheed Martin operated in US imperial units (e.g pound seconds). So, the course corrections produced by the guidance team were off by a factor of 4.45.

Somehow, with all the checks and tests, neither NASA nor Lockheed Martin realised their software were using different measurement units.

Whilst there were a multitude of other contributory factors, this was an expensive $327 million lesson in not assuming that what you say is always what the recipient understands. Or what you hear is always what the speaker means.

Trust but verify

Back in Issue #006, I wrote about the importance of clear communication in air traffic control. In that context, specific phrases have specific meanings to reduce misunderstandings. In a business context, applying that technique may not be that practical - especially given the versatility of language.

But the rationale for the technique is still valid when working with stakeholders.

Here's four general principles I apply with my stakeholders to help reduce the risk and the impact of misunderstandings:

Be honest and open about why I'm taking this approach and how it helps reduce misunderstandings. This helps ward off complaints about why there are so many questions and why there's so much repetition.

Expect that, on the first pass and especially with new stakeholders, they won't fully appreciate or understand what I mean. So check and repeat as needed.

Test my understanding of what my stakeholders are saying by asking clarifying questions so they can expound on what they are trying to convey. It also helps elucident their context, their intent, and what's driving them.

Do read backs both at key junctures in a meeting as well as at the end. This is invaluable in helping everyone get in sync and stay in sync. Especially if you rephrase with your own words or use a different format, like a diagram, to confirm your understanding.

Put another way: trust that what you're saying and hearing is in good faith and with the best of intentions. But always verify that everyone is in sync as best as they can.

🤔 Made me think

How different countries negotiate differently.

One area where misunderstandings can cause critical failure is in negotiating.

Especially when it's different cultures negotiating with each other. In his book, "When Cultures Collide", Richard Lewis - a linguist who speaks 10 languages, charts his findings about how each country typically negotiates.

British

The British tend to avoid confrontation in an understated, mannered, and humorous style that can be either powerful or inefficient.

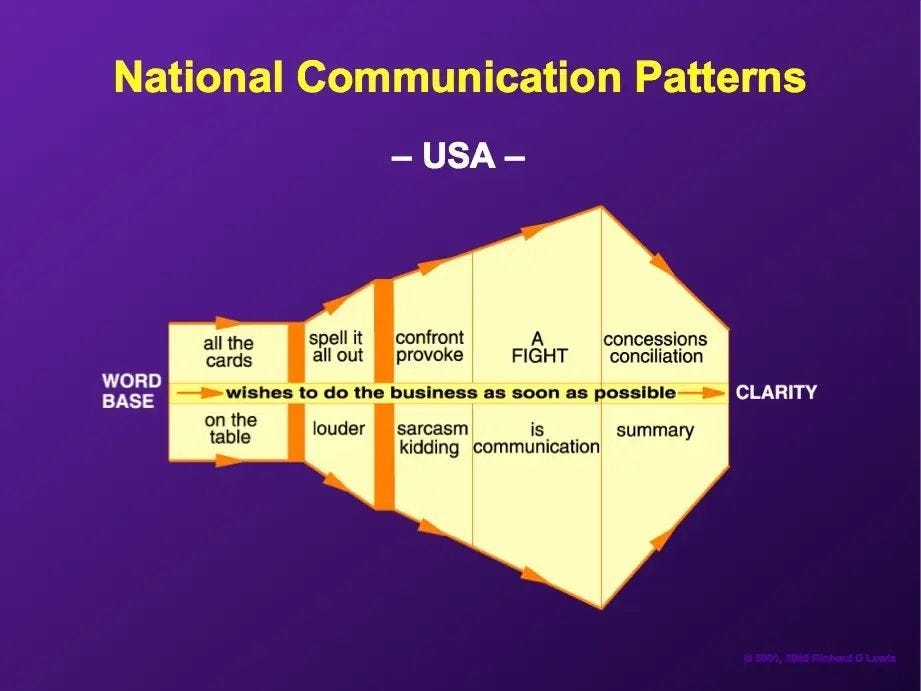

Americans

Tend to lay their cards on the table and resolve disagreements quickly with one or both sides making concessions.

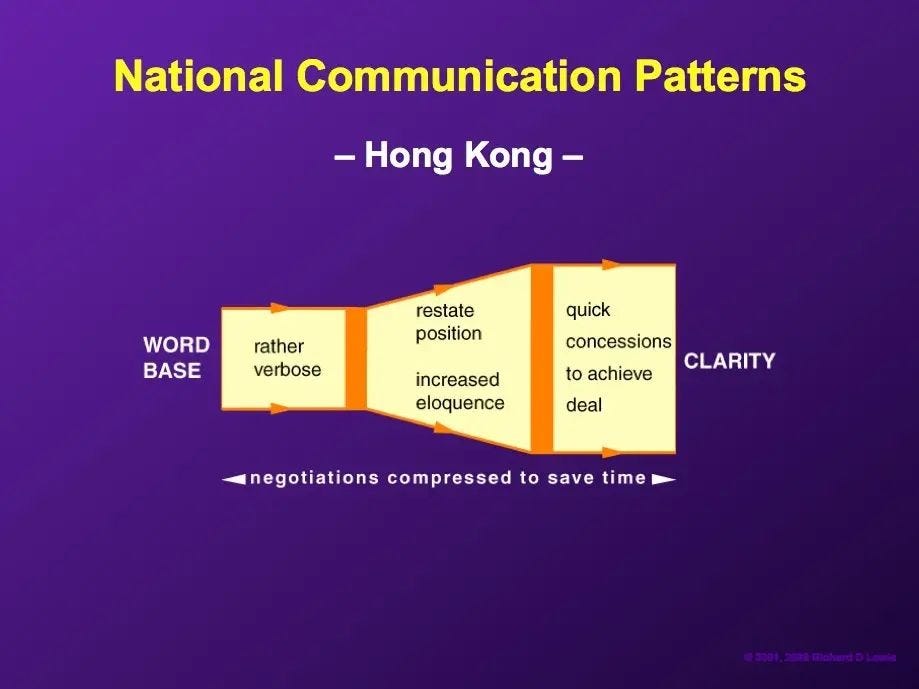

Hong Kongers

Tend to negotiate much more briskly to achieve quick results.

You can see more charts on Business Insider.

🧑💻Worth checking out

📺 The "Four Candles" sketch | The Two Ronnies

A sketch from the inimitable Two Ronnies way back in 1976. It hilariously demonstrates what you say isn't necessarily what's being understood by the other side. Especially if you're too concise!

🖖Until next Thursday ...

If you enjoyed this newsletter, let me know with the ♥️ button or add your thoughts and questions in the comments. I read every message.

And, if your friends or colleagues might like this newsletter, do consider forwarding it to them.

For now, thank you so much for reading this week's issue of The Forcing Function and I hope that you have a great day.

PS: Thanks to P for reading drafts for me.